Thanks Gillette. Why Men Should Aim To Be The Best They Can Be

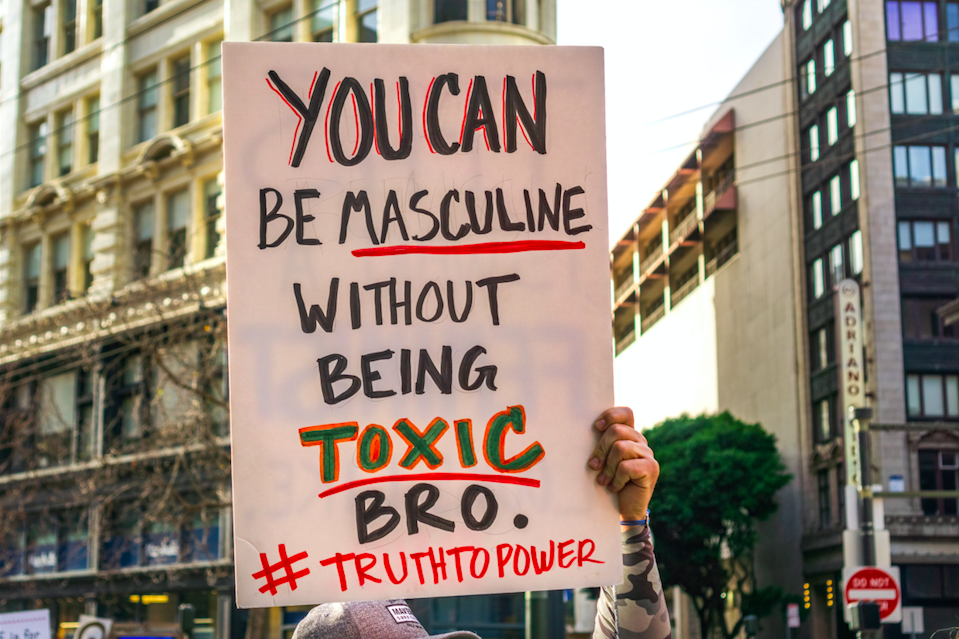

The recent Gillette ad caused a massive response for a 1:47 minute film. Is it the close shave we had to have, or one that’s just too close for comfort?

The ad actively highlights the importance of rejecting toxic behaviour, showing men intervening when others are harassed or bullied, and helping to protect children from the same behaviour. Promoting civility, care and protection can’t be bad. Can it?

Alignment with the #metoo movement may be enough to raise the red flag to some. But even, so, just why is the ad’s message so controversial? Gillette’s strapline change from ‘the best a man can get’ to ‘the best a man can be’ seems nothing short of genius. Why is it not universally inspiring?

Unfortunately, diversity initiatives are now well known to backfire and cause backlash. Any attempt to change people’s attitudes and beliefs will almost certainly do this. The history of Civil Rights in the US is an unfortunately good example.

Whether this initiative does or doesn’t result in unintended negative consequences for Gillette, there are lessons that can be learned from the response. At the heart of the contention is the portrayal of the toxicity of hyper-masculine cultures.

The key characteristics of a toxic masculine culture are:

- Show no weakness – don’t admit you don’t know, don’t express doubt;

- Show strength and stamina – stronger, longer, and bigger are better;

- Put work first – work hard, don’t let family interfere;

- ‘Dog eat dog’ – watch your back, you’re in or out.

These characteristics are traditionally associated with men’s work, and with leadership. They are prevalent in many industries and occupations, not just dangerous or physical strength-related ones, such as the military or emergency services. They also characterise engineering, construction, and white collar industries like finance, procurement and law. Many mainstream organisations conflate the demonstration of masculine traits with effective performance.

It’s not the characteristics themselves that are the problem. And it isn’t men either.

The problem with these characteristics is when they are the majority characteristics of an organisation’s culture.

An interesting feature of masculinity is that it isn’t ever settled, it always needs to be contested. The problem is not in the behaviour of individual men, but in workplace cultures that reward survival-of-the-fittest and dog-eat-dog competitiveness.

The expectations are neither inevitable nor are they universal. The nature of teams, the structure of work and the core tasks associated with specific occupations all moderate how cultures form and are experienced in male-dominated occupations. For example, where firefighting crews were encouraged to express camaraderie and work with good humour, they were much less likely to engage in high risk behaviour. They were faster to coordinate, had fewer accidents, and caused less property damage.

In one study of leadership climate, 56 per cent of people considered that the managers they interact with every day displayed toxic leadership to some degree. Masculine contest cultures are less inclusive, and there is a lower level of psychological safety. Higher employee stress, work-life conflict and turnover intentions result. Organisational commitment is low, as is wellbeing. The more toxic the culture, the worse performance becomes over time.

When men who strongly identify with masculine characteristics experience threats to their superiority, they also tend to reduce support for gender equality. If they see programs for gender equality (such as this ad) as a zero-sum game, ie, any gains to be made by women will be losses to them, they withdraw their interest, don’t get involved, or oppose the programs.

Moves towards equal pay, for example, are seen as reducing opportunities for men and placing downward pressure on men’s pay. In a contest culture where men are competing against other men, women’s access into the competition is seen as disrupting the advantage that men have. Attempts to increase the representation of women will be difficult.

It is when men who identify strongly with masculine characteristics perceive threats to their masculinity that they are more likely to sexually harass others. And they may harass either female or male colleagues.

Where men believe that gender roles are fixed, they tend to rationalise the social system. They are more likely to justify the system and its inequities. On the other hand, where men are primed to see gender roles as socially ascribed, their identification with ‘male’ decreases as does their defence of gender inequities. Their views align more with women’s.

A real part of the problem for change is that working in a masculine culture is associated with greater work engagement and job meaning for some men. Some men find the prospect of winning masculine status so seductive that they will sacrifice their wellbeing for opportunities to be in the contest.

Finally, a major challenge is that those organisations that need training the most are the least likely to benefit from it. Organisations that promote masculinity context cultures won’t change through traditional diversity and sexual harassment training. In such cultures, conventional approaches have not been effective and in some cases have backfired.

Diversity and sexual harassment training is only effective in those organisations that support its purpose and content. When there is misalignment, when training is done to meet external reporting or is tokenistic, training is at best a waste of time.

These issues highlight some of the reasons behind the strong, negative reactions to the Gillette ad.

If you are someone who sees the Gillette ad as a breath of fresh air, and you want to reduce the degree of masculine contest in your culture, keep these three key things in focus:

- Let people control their own solutions to inequities, by engaging them in the problem, make sure they are volunteers, and use curiosity as a key hook. This makes it rewarding

- Increase contact and connection between under-represented groups, and ensure they work together as this minimises status differences and focuses on work and learning;

- Make responsibilities transparent, and make people accountable for their actions, which taps into their desire to look good to others